Allen James Lynch, Medal of Honor recipient, speaks at Central

September 26, 2014

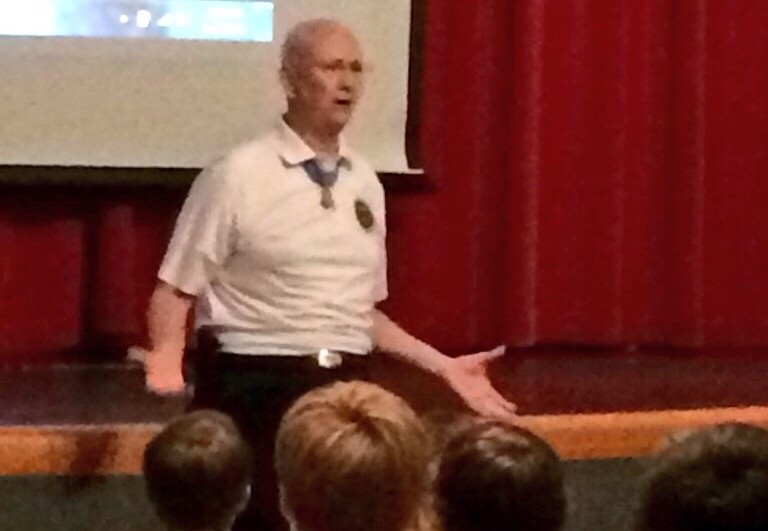

The Little Theater in Naperville Central’s basement was packed to the gills with students, almost every seat taken, to listen to Medal of Honor recipient, Sgt. Allen James Lynch speak.

According to the Congressional Medal of Honor Society, The Medal of Honor was first introduced in 1861 as a way to recognize extraordinary members of the navy, but during the following months, the wording was changed until President Abraham Lincoln signed off on the Army Medal of Honor.

The first Medal of Honor was awarded on March 25, 1863. According to the Congressional Medal of Honor Society, since then, there have been 3492 recipients and there are only 79 recipients still living today.

Prefacing Lynch’s talk, Humanities teacher Michael Bochenski said that the presentation wasn’t just about receiving the Medal of Honor.

“Having the guts and bravery to do what is right—that’s what this presentation is about,” Bochenski said.

Lynch was commended for his actions during the Vietnam War when he refused to leave members of his company behind when they were forced to withdraw under heavy fire. He maintained their position for two hours against an enemy that had far greater numbers and superior firepower, saving the lives of three wounded men.

“I stayed with them, rather than leave them behind, because that’s just not what you do,” Lynch said.

While his actions were very heroic, Lynch admitted that he wasn’t always that way. He was bullied from 3rd through 8th grade, and he said that impacted his self-image greatly.

“As I’m being bullied, I’m letting fear take me over,” Lynch said.

He said that he was afraid to get good grades because he didn’t want to stand out, but he was also afraid of the lecture he would receive from his father for getting poor grades. This mentality continued through high school, and after failing math twice and having to take summer school for two years to make it up, he graduated high school.

After high school, he managed to get a job, but Lynch said that he knew that he would get drafted. That was why he took control of his own destiny and ended up enlisting.

Lynch said that going to basic training was a huge shock. When he was growing up, he had grown up in an all-white neighborhood and had gone to a school that was all-white as well. He had never encountered diversity until he got to basic training where his drill sergeant was a big African-American man.

“We were all different, and we all had to work together,” Lynch said.

Having never seen anyone who wasn’t white before basic training was startling, but Lynch said that he moved past it.

“All this stuff that makes us different came down to one thing-can I trust you?” Lynch said. “That’s what I learned in Vietnam.”

When describing basic training, Lynch said at six in the morning the recruits would start physical training which started with a mile. He said that during this run, no one could drop out—or else they would have to run more.

“We did this until we understood that you never, ever, ever leave your buddies-ever,” Lynch said.

This lesson showed in his heroic actions in battle which earned him the Medal of Honor.

When he came back from Vietnam, Lynch ended up settling down with his wife in Gurnee, Illinois, and he said that he started to live the American dream. The United States governent, however, didn’t treat him as well as veterans are treated today.

“They told us, ‘keep your mouth shut, pick up your life, and move on’,” Lynch said.

It was this mentality that inspired Lynch to work for Veterans’ Affairs, and he advocated for benefits for disabled veterans. Since then, Lynch has retired, and he now travels giving talks like the one at Central.

After his talk, there was time for questions—and Lynch had many opinions to share with the students in attendance.

He had a strong opinion on the modern media, expressing his distrust of national journalists.

“There are too many people on television and in print who are more interested in their own political beliefs than in the truth,” Lynch said.

He also told students that he believes strongly in the draft.

“If it were up to me, I wouldn’t have any kid going to college without two years of military or social service,” Lynch said. “You don’t have a vested interest in this country if you haven’t served.”

All too soon, it was time for Lynch to wrap up his talk, and Bochenski ended the presentation with his final thoughts—he wants all of the students in attendance to apply Lynch’s lessons to their lives.

“I want you to be brave now,” Bochenski said.