Special focus: nine exceptions to freedom of speech

December 28, 2016

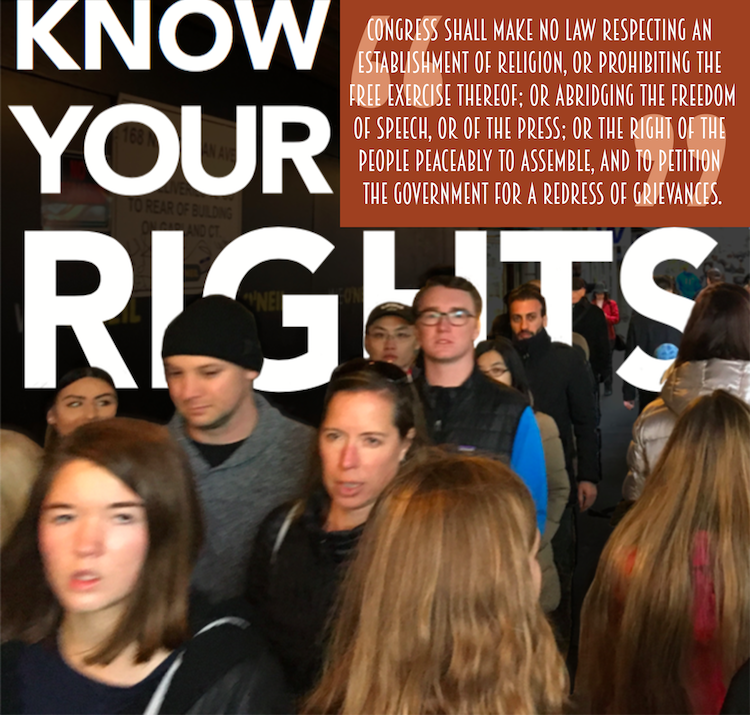

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

This is the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. It ensures the freedom of religion, speech, press, assembly and petition to American citizens. However, per two recent events, it appears as though some Americans do not understand what is and what isn’t covered under the First Amendment.

First, the CT ran a story titled “Freedom of Speech?” on centraltimes.org in November. That article, about a racially motivated altercation between two students, sparked outrage. As a result, the Central Times’ comments section was flooded with threats.

This prompted the CT to change its editorial policy (see bottom of page).

Second, On Nov. 29, Donald Trump tweeted his sentiment toward flag burning, calling for those guilty to receive a “loss of citizenship or year in jail!”

The Supreme Court ruled on this during Texas v. Johnson (1989), with the court writing, “If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the Government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable.”

If the president-elect is confused as to what is and isn’t free speech, other American citizens probably are, too.

Due to these two issues, the CT decided to outline the nine categories of speech that are not protected under the U.S. Constitution, as written by the Supreme Court.

- Obscenity

According to the Legal Information Institute, there is a three-part test to determine if something is obscene, called the Miller test. First, it must be determined if “the average person, applying contemporary community standards” could determine that, “taken as a whole,” the work “appeals to prurient interest.” Second, it must be determined that sexual conduct (defined by state law) is depicted or described in a “patently offensive way.” Thirdly, it must be determined if the work, “taken as a whole,” lacks “literary, artistic, political or scientific value.” If the Miller test cannot be passed, the speech is obscene and therefore illegal.

This test was developed after Miller v. California (1973) after Marvin Miller mailed “adult” ads to “unwilling recipients,” according to Oyez. The Supreme Court ruled that Miller’s mailing was unconstitutional and then developed the Miller test to further assess obscene material.

- Defamation

Legally, defamation is “the act of making untrue statements about another which damages his/her reputation.”

Further than this definition, there are two types of defamation: libel and slander. Libel is if a lie is written and slander is spoken. In both cases, defamation is taking place, but there is a distinguishable difference between libel and slander.

However, defamation becomes more difficult to discern if the content was of public concern or the subject is a public figure.

A public figure is, “at the very least to those among the hierarchy of government employees who have, or appear to the public to have, substantial responsibility for or control over the conduct of governmental affairs,” as written in Grossman v. Smart (1992).

Since Americans have the right to criticize those who govern them, defamation lines are blurred when it comes to public figures.

As established in Grossman v. Smart (1992), a defamation case must legally prove that:

“(1) defamatory language on the part of the defendant; (2) the defamatory language must be of or concerning the plaintiff; (3) publication of the defamatory language by the defendant to a third person; and (4) damage to the reputation of the plaintiff. If the defamation refers to a public official or public figure or involves a matter of public concern, thus invoking First Amendment protection, two additional elements must be proven as part of the prima facie case. The plaintiff must prove (5) the falsity of the defamatory language and (6) fault on the part of the defendant, in addition to the four elements mentioned above.”

Essentially, for public figures, defamation only takes place when “actual malice” is intended. “Actual malice” is defined as “knowledge that the information was false” or that information was published “with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.”

- Expression intended to incite lawless action

Inciting imminent lawless action is another category of speech that is not covered by the First Amendment. In Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), in which a KKK member called for a group of people to act in violence, the Supreme Court wrote that “the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.”

- Fighting words

In 1942, Jehovah’s Witness Chaplinsky called a city official a “God-damned racketeer” and “a damned fascist.” The case went to the Supreme Court and the Court determined that Chaplinsky’s words were not protected under the First Amendment since they were said to “inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.”

If the average person could be incited to violence because of someone’s words, those words are not protected under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

- Unwarranted invasion of privacy

The rise of computers and computerized databases occurred in the early 1970s, which resulted in a concern from American citizens about their privacy rights. The United States responded with the Privacy Act of 1974, which, according to the Department of Justice, “establishes a code of fair information practices that governs the collection, maintenance, use, and dissemination of information about individuals that is maintained in systems of records by federal agencies.”

The Privacy Act has three guaranteed rights: (1) one’s right to see personal records, (2) one’s right to request changes to records that are not “accurate, relevant, timely or complete” and (3) one’s right to be safeguarded from unlawful “collection, maintenance, use and disclosure of personal information,” according to the Department of Justice.

Essentially, the Privacy Act of 1974 ensures that one’s personal information stays personal. If personal files are publicly disclosed and thus “would harm the individual concerned,” then that would be a violation of privacy and could not be protected under the First Amendment, according to Cornell University.

- Deceptive or misleading ads/ads for products or services illegal to minors

Free speech and advertising has historically been a cloudy issue for the Supreme Court and overall, advertising has achieved a large threshold of free speech.

The issue was first introduced in the court case Valentine v. Chrestensen (1942). In this case, Valentine was advertising his WWI submarine that sailed from port to port. Many of his fliers ended up littering the streets of New York. As a result, New York tried to quell Valentine’s advertising by enacting a ban on the use of city streets for commercial marketing. In response, Valentine took the price off his handbills, thus taking away his “commercialism.” He printed a petition to New York’s new ban on the backside of his brochures after a city official told him that speech would be protected under the First Amendment. This case ended up in the hands of the Supreme Court who created the “first commercial speech doctrine,” according to the First Amendment Center. This doctrine exempted commercial speech from first amendment protections and ruled Valentine’s actions unconstitutional.

After Valentine, an abundance of cases followed, protecting commercial speech more with each case. The court reasoned that “speech is not stripped of First Amendment protection” since it includes commercialism, “people will perceive their own best interests if only they are well enough informed and … the best means to that end is to open the channels of communication, rather than to close them.” Additionally, Justice William J. Brennan, Jr., wrote “the fact that protected speech may be offensive does not justify its suppression.”

In 2001, these rulings culminated in Lorillard Tobacco Co. v. Reilly. In this case, the Supreme Court ruled that the state of Massachusetts could not regulate tobacco advertising.

However, despite these favorable First Amendment rulings in advertising, companies to not have free speech. Established in 1913 by Woodrow Wilson, the Federal Trade Commission Act requires that “(a) Advertising must be truthful and non-deceptive; (b) Advertisers must have evidence to back up their claims; and (c) Advertisements cannot be unfair.”

- Clear and immediate threats to national security

Often referred to as “clear and present danger,” this category of speech not covered under the First Amendment is well-known. A common example includes shouting “Fire!” in a movie theater.

One of the first times the “clear and present danger” wording was used was in Schenck v. United States (1907). During WWI, Schenck was arrested after giving out anti-war and anti-draft propaganda. The case made it to the Supreme Court, with Schenck using the First Amendment as his defense. Ultimately, the Supreme Court ruled against him, with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes writing, “The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.”

While Schenck’s pamphlets would have been legal during peacetime, his actions during wartime threatened national security and thus were ruled unconstitutional.

- Copyright violations

Defined by Merriam-Webster as “to steal and pass off (the ideas or words of another) as one’s own, to use (another’s production) without crediting the source, to commit literary theft [and] to present as new and original an idea or product derived from an existing source,” plagiarism is a heavily talked-about problem that often appears in the school system. In fact, according to plagiarism.org, when Josephson Institute Center for Youth Ethics surveyed 43,000 high school students in public and private schools, it found that one in three students had plagiarized an assignment.

Copyright law is not clear-cut. There is no “magic number or percent” for the amount of work that can be borrowed and re-used, according to Frank LoMonte, First Amendment lawyer and head of the Student Press Law Center. Often, there are claims that a certain length of a song or video can be used without credit as well as a certain amount of an image. While this is true (called the “Fair Use Doctrine”), LoMonte says there are no hard and fast rules for these “numbers.” Additionally, simply giving credit to the creator does not mean one can use a piece of work, further complicating copyright law.

One safe, always legal way one can borrow work is through a review, critique, commentary or parody. Other than that, the laws of copyright vary depending on who you are, how much of the work is used, the purpose of the work being used and the effect your work has on the original, according to LoMonte. (For more information on copyright law, visit copyright.gov.)

Ultimately, copyright law is violated, purposefully or accidentally, almost as often as the speed limit. Yet, it is still illegal and not protected under the First Amendment.

- Expression on school grounds

In December 1965, A group of students decided to wear black armbands to school to protest the Vietnam War. The students were sent home after district administration created a policy inhibiting the student’s ability to wear the armbands. The students did not return to school until Jan. 1 when they had planned to end their protest.

With the help of their parents, the students sued the school district for infringing upon their First Amendment rights. The Supreme Court, in Tinker v. Des Moines (1969), ruled in favor of the students, with Justice Abe Fortas writing that a student’s actions must “materially and substantially interfere” with the school day in order for his or her First Amendment rights to be infringed upon.

Since students’ free speech can be curbed if it causes a “substantial” disruption to classroom activities, student speech is not fully protected under the First Amendment.