Lifelong learners

How advanced degrees are furthering teacher careers and student learning

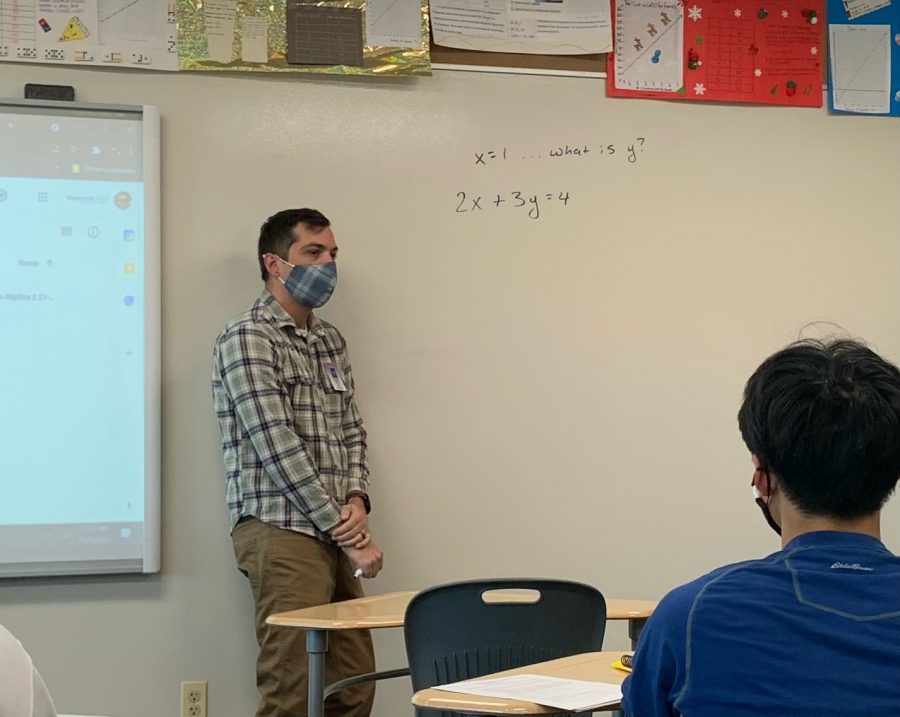

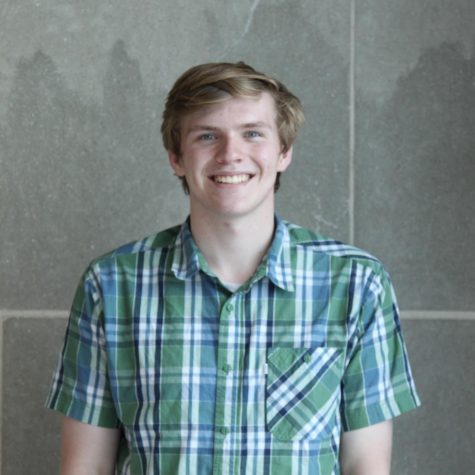

Nick Straka is a student in pursuit of his doctorate outside of his job teaching several levels of algebra at Naperville Central.

November 29, 2021

During the day, Nick Straka teaches his students at Naperville Central algebra and multivariable calculus. At night, he becomes the student, listening to lessons about curriculum instruction.

Straka is just one of many teachers at Naperville Central in the process of working toward a graduate level degree. After having spent seven years getting his bachelor’s and master’s degrees, Straka is pursuing his doctorate in curriculum and instruction with an emphasis on STEM, or science, technology, engineering and math.

He spends about 15 hours a week on online night classes with Texas Tech University.

“It’s been really hectic this semester,” Straka said.

About two-thirds of teachers at Central hold a Master’s degree or higher, according to the 2021 Illinois Report Card. Nationally, 56.4% of teachers held a master’s degree or higher in the 2011-2012 school year, statistics from the National Center for Education Statistics showed.

“When I was first hired at my school, I was the only person in the entire English department who did not have a master’s degree,” said Dr. Tim Dohrer, Director of Teacher Leadership and Assistant Professor at the Northwestern University School of Education and Social Policy. Dohrer used to teach at New Trier High School, where he was later English department chair and principal.

One of the reasons so many educators pursue further degrees is financial incentive.

“Most public school teachers work under a contract that gives them more money if they take more classes,” Dohrer said.

In Naperville District 203’s teacher contract, for instance, there are nine “lanes,” categories of pay based on how much coursework a teacher has completed. The salary schedule starts at a bachelor’s degree lane and increases in pay all the way to the master’s plus 54 credit-hours lane.

The idea is for salary lane changes to offset initial tuition fees, which can be very expensive. Many school districts, though not District 203, also directly subsidize a part of those costs.

“It’s probably going to take a couple years after I finish to recoup that cost,” Straka said. “Probably three or four.”

Obtaining graduate degrees can also open up new teaching opportunities beyond the Naperville Central campus.

“A Ph.D will give me the ability to maybe teach science at a college or something with teacher education,” science department chair Katherine Seguino said. “My professors right now are strongly encouraging me to do journal articles and going to conferences once it becomes available.”

In the classroom, higher degrees can make a big difference for students as well.

“It can be this broad content or teaching improvement,” Dohrer said. “Those teachers that go on and get a reading specialization or become a second language instructor may also work with a new group of kids.”

Some higher degrees in education also have to do with behind the scene organization and peer leadership.

“[If] someone gets a master’s degree in teacher leadership, we expect that they’re going to go out and start coaching other teachers, volunteering on committees, get engaged with their families and communities in a way that’s going to make the whole school better.”

Teachers working toward their doctorate also conduct independent research into areas they’re interested in. They can implement their findings in their classrooms, departments or even the whole school.

“I’m in the writing phase of my dissertation,” Seguino said. A dissertation is the final extended topic paper students produce before obtaining their doctorate. “I’m also going to produce a product, a small-scale curriculum manual to present to school leadership.

“My focus is on environmental education. That not only belongs in science, it belongs in every single course.”

For Straka, who still has a few years to go before completing the 63 required credit-hours of work for his doctorate, there are a lot of questions he’s interested in exploring for his research.

“One of them is: does teaching math through a historical and cultural context increase motivation into learning content?” he said. “The other one I have is inquiry-based learning, where students are introduced to concepts informally at first, almost through conjecture.”

Straka hopes the first option can make math and science more appealing for students who might be more focused on humanities, benefiting his instruction and student engagement.

“I think if I went that route, it would influence the way I teach on a daily basis, with the hopes of maybe even creating a new class,” he said.