Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, standardized testing scores fell across the board. That probably makes sense; students were kept out of the classroom for months and could only learn through a screen, so they probably didn’t grasp material as well.

But once kids got back to an in-person learning environment, scores should have begun to rebound, right? Well, at least for the math portion of the SAT, the data says otherwise.

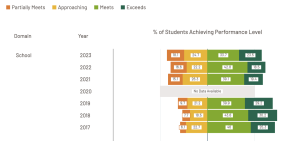

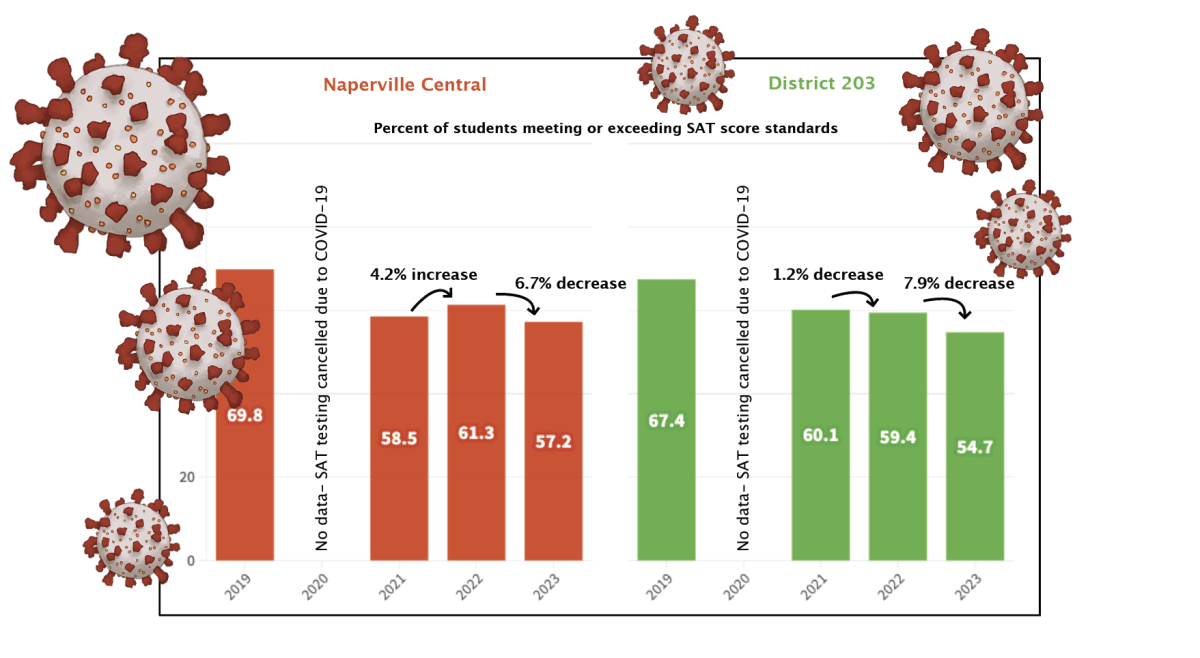

According to the Illinois Report Card, District 203’s percentage of students meeting or exceeding standards on the math section of the SAT dropped by 7.3 percentage points over the course of the pandemic, before dropping by just 0.7 percentage points from 2021 to 2022. In 2023, however, the number dropped by 4.7 percentage points. That pattern was followed at the state level as well: a large drop over the pandemic, followed by a small one and then a much larger dip in 2023.

Central’s data may subvert expectations even more: from 2021 to 2022, the rate of students meeting or exceeding expectations improved by 2.8 percentage points, before dropping by 4.1 points the next year.

This pattern begs a simple question: Why? Why did scores across the state follow this pattern? Why did 2023 SAT-takers perform more poorly across the board than in 2022?

The Drop

The 2023 SAT data provided by the Illinois Report Card is taken from the school-proctored SAT exams that every junior in the state takes in mid-April. The 2023 scores that exhibit such an odd pattern are all from exams taken by current seniors.

Three years ago, current seniors were freshmen, navigating the online and hybrid learning world of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We found [the pandemic] had a huge impact on understanding of students that were in Algebra 1, which the majority of our students took in ninth grade,” math department chair Scott Miller said. “Being online had a big impact in terms of their mathematical foundation moving forward. So there’s a lot of missed learning opportunities.”

Algebra-based questions make up a bulk of the SAT math section, meaning students who took the test last year missed out on in-person instruction in a class key to performing well.

“If [Algebra 1 and 2] aren’t your best experience because of the effects of the pandemic, then naturally you’re going to feel the effects when you’re sitting down to take an assessment like the SAT,” said Steve Jeretina, Central’s Assistant Principal for Curriculum and Instruction.

The Class of 2023, who took the SAT in 2022, were in geometry classes during the pandemic, which may be why their scores weren’t as adversely affected.

Learning algebra was more difficult during the pandemic, certainly, but that may not be the only reason that the Class of 2024 struggled on the SAT.

“I also think that the scores went down that year because I felt that kids didn’t have the endurance to learn math,” said Deb Danbom, an Algebra 1 and Algebra 2 teacher at Central. “It was really hard for a kid to sit and take notes on a lesson or do a homework assignment that takes 30 minutes. That was a huge struggle. I don’t think that they were used to having a full class period, being expected to engage in a group or produce work within the classroom. I think that was a struggle. That translates not just in their skills, but in taking a standardized test for. I just don’t think that they could do it.”

“I also think that the scores went down that year because I felt that kids didn’t have the endurance to learn math,” said Deb Danbom, an Algebra 1 and Algebra 2 teacher at Central. “It was really hard for a kid to sit and take notes on a lesson or do a homework assignment that takes 30 minutes. That was a huge struggle. I don’t think that they were used to having a full class period, being expected to engage in a group or produce work within the classroom. I think that was a struggle. That translates not just in their skills, but in taking a standardized test for. I just don’t think that they could do it.”

According to Miller, student collaboration was also impacted by online learning. It’s a lot easier to work together across a table than across a computer screen, so kids largely missed out on working together while online.

For one senior, the computer-screen barrier posed an elevated challenge.

“I think it’s harder to get a grasp of the information when the teacher isn’t in front of you and isn’t giving the inference information directly,” said senior Rowan Schmidt, who took Algebra 1 as a freshman during the pandemic. “It’s hard when you’re just looking at the screen for so many hours. I had math pretty late in the day, so I was just exhausted by then I couldn’t get the information. I was struggling pretty hard [on the Algebra 1 section].”

For others, the way math classes are structured was the problem, not having been required to learn online as a freshman.

“I don’t think I don’t think that [struggling in Algebra 1] was the case for me,” said senior Heather MacDonald, who took Algebra 1 as a freshman during the pandemic. “But it is hard building off of concepts that you learned so long ago, and it’s hard taking that to the next level if you’re not taught what the next level is until too late. In precalc, there’s a greater emphasis on solving the problem by looking at different methods. Algebra 2 wasn’t really like that. I wasn’t bad at Algebra 2, I just, I just think that you can’t do well on the SAT without progressing through an actual precalc course.”

Of course, that likely isn’t the reason why the Class of 2024 in particular struggles — 2023 grads didn’t have an extraordinarily different curriculum — but the way math course progression is designed may have harmed some students more than others.

What does it mean?

From college applications to tracking student understanding of math and English, SAT scores have a variety of uses. So what does a 4.1 percentage point drop in scores ultimately mean for the Class of 2024?

Well, according to Miller, not that much.

“I wouldn’t say to anybody that your SATs score defines who you are in life,” Miller said. “But perseverance and [knowing] how to access resources is much more important. That’s a lifelong skill in anything that you walk into, and I think collaboration is another piece. I think that’s the piece I wonder about for [the Class of 2024], what is the level of collaboration like, because it was more isolationist [during the pandemic].”

Indeed, the concentration and collaboration skills that Miller and Danbom believe had an impact on SAT scores may have a larger impact on a student’s future than a poor performance on the SAT.

“The biggest piece of whether a student continues in college is if they developed some perseverance,” Miller said. “That’s really what it is, it isn’t a test score. I’ve seen graduates who have done really well on standardized tests, but their wherewithal and independence isn’t strong, and then they haven’t done well in college then as a result.”

Recovery

It’s been eight months since the COVID-19 pandemic officially ended, and two-and-a-half school years since students were learning exclusively online. The impacts of the pandemic are certainly still clear, be they in SAT performances or in student behavior and attention span.

The recovery to pre-pandemic performance levels is a long, winding road. For Central, it starts with support systems.

The recovery to pre-pandemic performance levels is a long, winding road. For Central, it starts with support systems.

“We’re using what we call interventions at the Tier One level — the classroom level — and the Tier Two level — which might be something along the lines of a math support during the students lunch period — more effectively,” Jeretina said. “The last time that I looked at the data for our math lunchtime support from the start of the school year through Nov. 15, that team of teachers has worked with 206 students to get them to where they need to demonstrate proficiency. I would like to think that that is going to result in improved confidence and performance in that classroom, which in turn should result in improved scores when they get to the SAT.”

Central’s math department also added a full time staff member devoted to helping students perform better in the classroom.

“There was some funding available to create some new positions [in the department, such as a] math interventionist,” Miller said. “They continue working to refine how we help students in terms of success in the classroom in terms of intervention. It’s really systemic that way. Overall, that’s helped the success that we’re seeing in the classroom for students.”

As for the softer skills students develop in math? Well, some new policies at Central may be helping students to better develop them.

“I found this year that by having cell phones away [during class], we’ve taken away the environment that we’ve created that lends itself to isolation,” Miller said. “Now we created more, let’s get back to some face to face communication, and some collaboration, for students to be able to communicate more on an interpersonal level. I think that’s the piece to see moving forward.”

It remains to be seen if these supports and policies will make a difference in student performance, but students are already starting to do better in Algebra 1 classes.

“I definitely see an improvement this year,” Danbom said. “I feel my Algebra 1 students are stronger than they have been in the past because now they’ve been in person through junior high which is when the math gets more algebra. They’re getting stronger.”

This article is the first of a series that examines the lingering impacts of COVID-19 on education across Central’s academic departments.

Amanda • Aug 18, 2024 at 11:13 am

There is now a wealth of evidence that covid causes brain damage in even “mild” cases. Schools will want to look at hepa filters if they want their kids to reach their best potential.