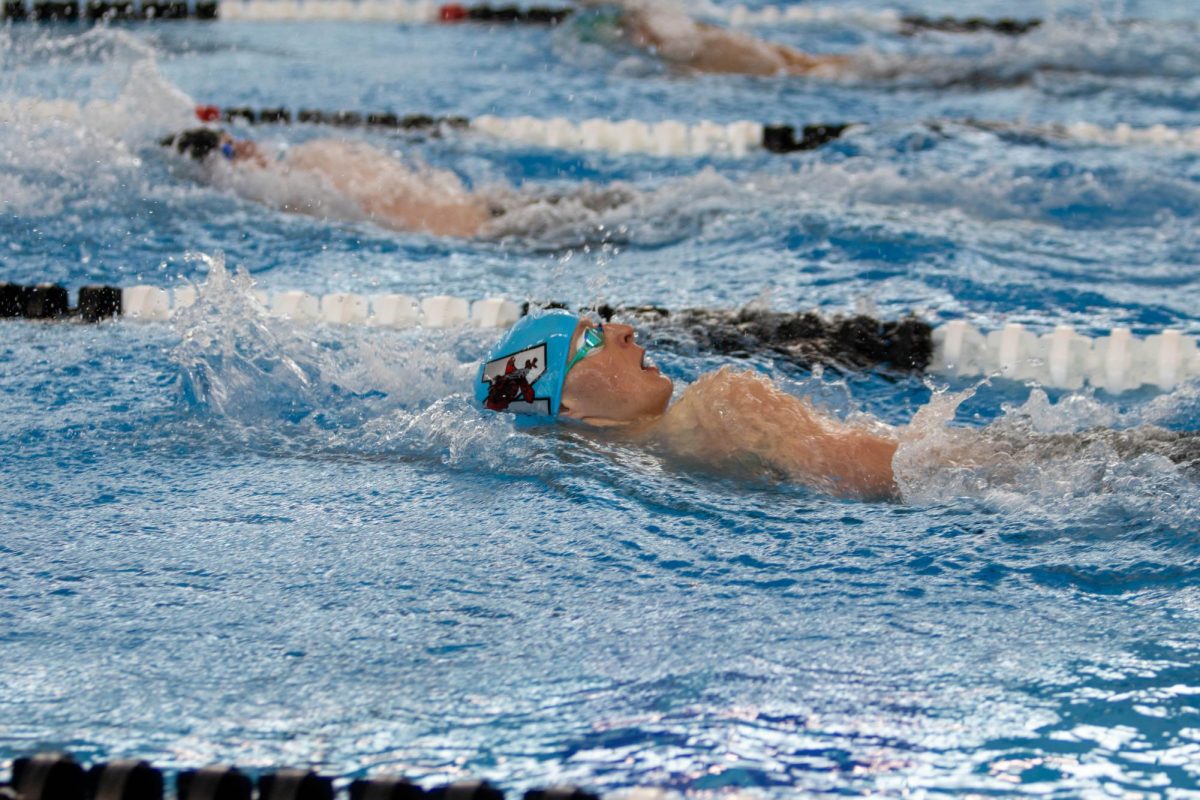

It’s 5:15 a.m. The sun has barely risen, but Naperville Central varsity swimmer Sarah Taylor is already in the pool, starting the first part of a long day of practices. She swims until 7 a.m., changes, eats breakfast and heads to class. Once the final bell rings to end of the school day, she’s back in the pool for her second practice of the day, swimming until 5:30 p.m. After that, she heads to an hour of lifting with her team before she’s free to head home.

The long hours of practice have been a part of the culture of competitive swim in Naperville and the broader Chicagoland community for years. However, trends in mental health and injury awareness have spurred many, including Taylor, to take a step back and look at how high school athletics operate. At what point does practice turn problematic?

According to research published by the Samford University Center for Sports Analytics, over 1.35 million young athletes suffer severe injuries related to their sports. Overtraining is a major contributing factor to this extremely high number. Athletes are pushed to their limits – then beyond that – in order to win.

“We know for a fact that a lot of the injuries we see are from fatigue,” said Mark Florence, Central’s head athletic trainer. “When the neuromuscular piece [of the body] starts to get tired and slows down, we start seeing some injuries.”

According to Florence, there is no “concrete line” when it comes to the right amount of time spent by high school athletes on practice and training.

“Your physical and mental maturity might be different from someone else’s, and that plays into it,” Florence said. “It has to be very individualized.”

As it stands, there are zero restrictions at the Illinois or federal level for the number of hours per week coaches can schedule for practice, training, conditioning and games. Many other states have set restrictions for the number of contact practice hours for high school football in an effort to prevent concussions and other head injuries. Additionally, California restricts high school sports teams to four hours of practice per day, with no more than 18 hours allowed per week.

So much of the culture surrounding sports, especially in high school athletes, revolves around the intensity of practice and training even if it’s unhealthy. It’s become a widely accepted reality of high school sports across the country.

“There’s a culture aspect [to] sports,” Florence said. “The culture of swimming is all about the yardage. Are there going to be people that can handle those intense practices? Yes. Are there going to be people that can’t and should be scaled? Yes, and I would hope and assume that coaches are doing that.”

For many years, Central’s swim program has been known throughout the community for its long practices with many early mornings.

“To the best of my knowledge, we have the longest hours and the most yards in the state for any high school program,” said Brian Schlesinger, a senior on Central’s varsity boys swim and dive team. “I think it’s just Coach Mike [Adams’] style, right? A lot of the time, he’ll push us to our extremes. We all reach a breaking point somewhere, but it has very much proven to be effective. We always perform well for state, we always perform well for sectionals, and at the end of the season, that’s his goal.”

For Taylor, though, the effects have not been as positive..

“If you’re being overworked, you don’t increase your performance by practicing that much,” Taylor said. “It also affects your sleep, which has an impact on your mental and physical health.”

Taylor said that the effects of overtraining on student athletes’ mental health is a widespread issue.

“I noticed that in the middle of the season, when we have a ton of practice, the mental health just goes down for the whole team,” Taylor said. “[I realized] this clearly isn’t a ‘me issue.’”

For Schlesinger, intense swim practices can be tiring, but are ultimately worth it.

“Sometimes [practices] will drag, especially over winter break, when it gets really long, but I’m happy for it because it’s kind of shaped me into the person that I am today,” Schlesinger said.

The issue of overtraining isn’t limited to just long days of practice. According to Florence, athletes who choose to specialize in a singular sport put themselves at higher risk of overtraining-related injuries.

“There’s a lot of research from the University of Wisconsin on sports specialization,” Florence said. “If I’m a youth sports kid and I’m going to do one sport all of the time, we’re seeing this contributing to overtraining.”

According to a study by the Boston Children’s Hospital, single-sport athletes spend almost twice as much time each week training as those who play multiple sports. Trends in specialization in a singular sport are major contributors to injuries in high school athletes. When a student athlete is training the same sport year-round, they use the same muscle groups in the same movements over and over again, contributing to overtraining. This can lead to breakdown in the muscles and joints, as well as mental fatigue and burnout.

“The research shows and the experts of the field in sports injury say youth should have a minimum of six months off of their sport of a singular sport,” Florence said. “We need seasons off for our body to rest, recover and repair itself.”

On the other hand, multi-sport athletes can also experience issues with overtraining, making for a very fine line in the right amount of practice.

“I’ve seen it in this area when athletes try to do two competitive sports in one season,” Florence said. “That’s not healthy…mentally, physically. If I have a day off from [one sport], but I spend that time training [for the other sport], I’m not getting a day off, and we know for a fact that our body repairs and gets stronger and faster with rest.”

The line between progress and regression is extremely blurry when it comes to high school athletes, so what can athletes do to ensure they avoid crossing it? It begins with the coaches and trainers.

“We have to be intelligent in the way that we’re designing programs, because we can’t have a cookie cutter,” Florence said. “With a lot of our overtraining injuries, we need to scale back. Sometimes we need to take a couple steps backwards to move forward.”

The biggest challenge is spreading awareness of the dangers of overtraining with student-athletes in order to ensure that they are taking care of themselves.

“What it comes down to is the athlete has to understand and listen to their body, and advocate for themself,” Florence said.