District 203 data reveals minority students face disproportionate rates of punishment

April 14, 2022

Naperville Central sophomore Jibran Haseeb and some friends huddled together in the school cafeteria during lunch in early December 2021. Bored, Haseeb decided to make a TikTok with a friend, featuring a series of clips of the duo going up to students in the lunchroom and pointing at them. The TikTok was posted to Haseeb’s account.

It was typical for Haseeb, who routinely takes to the platform to make comedic videos with his friends.

Several days later, however, Haseeb walked into Central and was called into the office by his dean, Jennifer Prerost. According to Haseeb, he was informed at this time that another student alerted Prerost to his video, and he was to incur a school-issued consequence for making it. To him and his family, the punishment felt “unfair.”

“It was just for fun,” he says. “I’ve never had hate for it before. Right away, I’m like, I can delete it if you want because I’m never ever going to try to cause more trouble than there needs to be.”

Haseeb, who is ethnically Black and Indian, left the dean’s office with an in-school suspension for recording in school without consent. His friend, who is white, received a Saturday detention.

“The only way [to get] an out-of-school suspension is if it’s a disruption to the learning environment or a threat to the safety of others or yourself,” dean Pete Flaherty said. “Anytime there’s an in-school suspension or out-of-school suspension, the four deans here at Central are meeting and talking as well.”

The progression of consequences at Central is typically a conversation, followed by a detention, Saturday detention, in-school suspension, out-of-school suspension, and finally expulsion.

In Haseeb’s case, Prerost confirmed that multiple deans, principal Bill Wiesbrook and Chala Holland, assistant superintendent for secondary education, were consulted in the decision.

“Students are protected to not be videotaped and pictured during the day, much less have that be posted on any type of social media with a negative connotation to it,” Prerost said. “When that occurs, the school gets involved because it negatively impacts the school climate.”

Prerost said that the discrepancy in discipline for Haseeb and his friend “had nothing to do with race or ethnicity,” but rather “their involvement in the situation.”

She could not specify what the differences in involvement were.

However, Haseeb feels he received a harsher punishment because of his race.

“I’ve had Black friends get in trouble for being in the halls, when I also had white friends that do something worse and they don’t get in crazy trouble at all,” he said.

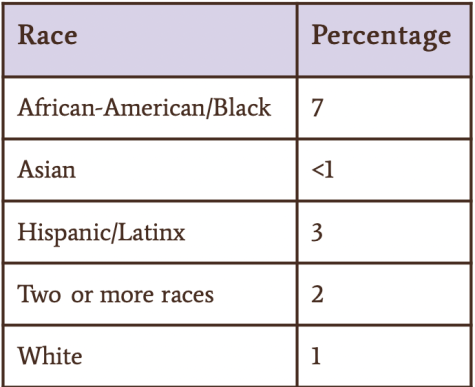

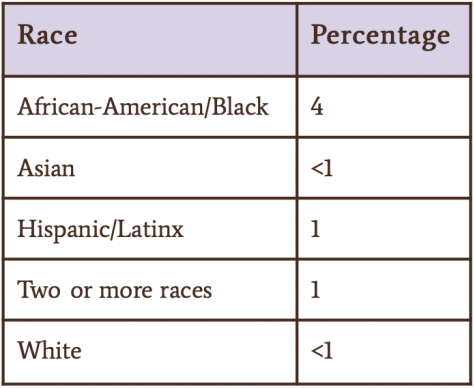

At a district board meeting on Feb. 22, District 203 acknowledged that these discrepancies do exist. Holland and the board administration detailed how “African-American/Black, Hispanic/Latinx, economically disadvantaged and students with disabilities are at a higher risk for a suspension of any type” in the district.

In the meeting, Holland said that the Equity Project found in 2014 “little to no evidence” that “Black students in the same school or district engage in more seriously disruptive behavior.” District 203’s consistent disproportionality has prompted further investigation into disciplining practices.

“I do think that we are decision makers,” said Dr. Rakeda Leaks, executive director of diversity and inclusion at District 203. “It is quite possible that we might be contributing to the outcomes that we see before us, which is why we’re looking into it.”

The district plans to take on a more individualized approach to discipline, working closely with students and their families to determine underlying causes of certain behaviors and a student’s “unique circumstances,” Leaks said. She also said the district is continuing to offer “implicit bias training” for staff, particularly for substitute teachers.

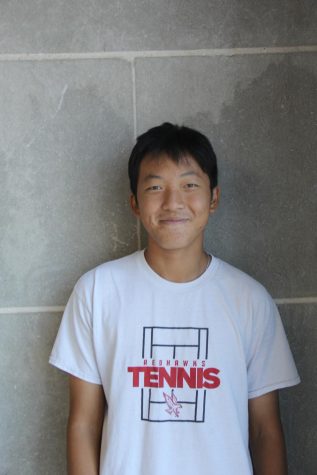

The emphasis on implicit bias training is welcome news for students like

sophomore Sahil Kumar. In Kumar’s experience, the disproportionality in races disciplined across the district doesn’t “necessarily stem from the dean,” but rather from “faculty and staff within the school.”

“[Deans] generally follow a strict protocol from the redbook,” Kumar says. “I think it more comes from the teacher’s decision to write you up.”

In fact, implicit biases of teachers often go beyond race or ethnicity and into common stereotypes in the classroom.

“I feel like a lot of times, students who generally fit a stereotype of someone who tends to not pay attention in class or seems disruptive… they’re met with more hostility,” Kumar says. “They tend to get in trouble more often than a student who the teacher would view as a scholar.”

The solution, Haseeb believes, is for teachers to proactively reach out to students and warn them before a suspension is warranted. This way, he says, the teacher can be viewed as “an ally” rather than someone out to get them.

In Haseeb’s experience, Central social studies teacher Todd Holmberg has been the only one to do so. If a classmate “seems like he’s not okay,” Holmberg will ask: “Is there a reason why you’re not turning in these assignments? Is there any way I can help you not get tardy to class?” Haseeb said.

While the district does acknowledge the possibility of bias on the part of teachers leading to disproportionality, Leaks says there are more factors at play.

“I don’t think there’s one thing that’s to blame,” she said. “Students have to take some responsibility in their actions but adults [should] create conditions where students feel safe. And it might be the way that these policies are written that might adversely impact some groups more than others.”

To foster a safe environment, Leaks says the district’s intent is to “have more conversations with students who are experiencing discipline at higher rates.”

“It’s more so just making sure we build real authentic relationships with the families and they see us as partners,” Leaks said. “We might have to do some things a little differently.”

In the future, Haseeb would like to see more “minority faculty” for more mutual understanding between teachers and students. In cases involving the use of racial slurs, for example, he said a cultural “disconnect” could cause white teachers to administer inappropriate consequences.

“If you’re not Black, you’ll never understand how demeaning it is to be called the N-word,” Haseeb said. “There should be more Black administrators in power who deal with situations like that because they have a connection with the student. The big thing is to be able to connect with your students.”

Raymond Hull • Apr 14, 2022 at 2:13 pm

In the south during forced integration the black schools were closed down. The teachers were not allowed to transfer into the white schools and any conflict involving white and black students usually resulted in discipline for the latter. 50 plus years later not much have changed with staffing and or discipline . No amount of training will change will the bias many of the teachers bring to the table.