The hidden homeless: Thousands of schools are failing to identify students experiencing homelessness

Students experiencing homelessness are guaranteed supports by law. But first, they need to be identified.

May 26, 2023

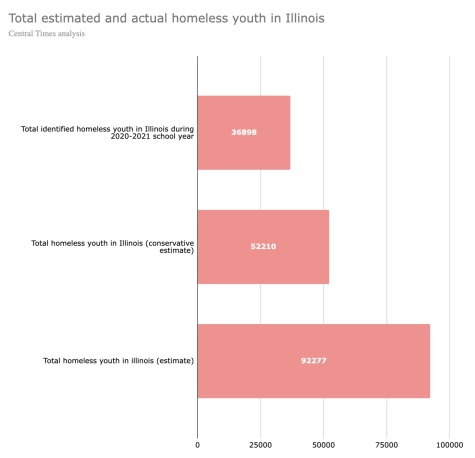

While Illinois identified about 37,000 students as homeless in the 2020-2021 school year, a Central Times analysis of state and federal enrollment data estimates there are up to 55,000 more students who haven’t been identified.

At least 87 school districts — from urban districts where free school lunch is the norm to affluent suburbs and rural communities — failed to identify any students experiencing homelessness, despite having significant low-income student populations. More than 500 of the state’s 868 school districts were “very likely to be undercounting homeless youth,” with an additional 200-some “likely to be undercounting homeless youth.”

Our analysis also found that the reported rate of student homelessness does not correlate with the percent of low-income students in a district. It’s evidence that the official count is wrong, said Jennifer Erb-Downward, Senior Research Associate of Poverty Solutions at the University of Michigan.

“There should be a correlation between poverty and homelessness,” Erb-Downward said. “[In Illinois], there’s really not much of a strong one, and that’s a pretty strong indicator that the data is wrong. In my view, that’s evidence of under-identification.”

The reasons for the routine under-identification of youth experiencing homelessness involve a population so hidden it’s often forgotten, laws so unknown few know how to access help, and non-existent enforcement that allows those responsible for implementing the law to cut corners.

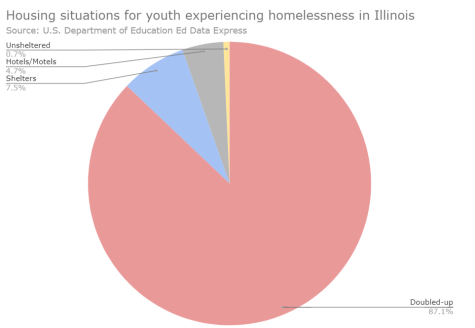

The U.S. Department of Education defines a student as homeless if they “lack a fixed, regular and adequate nighttime residence.” This definition includes students who are “doubled up,” also known as couch surfing, living in shelters or transitional housing, or sleeping on the street.

The McKinney–Vento Homeless Assistance Act, a federal law which passed in 1987, guarantees supports for students experiencing homelessness, such as free school lunch, a streamlined enrollment process and free transportation. But first, students need to be identified, and that responsibility lies on schools.

“It is legally the responsibility of the [school] district to proactively identify students who may qualify and not wait for them to identify themselves,” a spokesperson for the Illinois State Board of Education (ISBE) wrote in an email.

Still, despite what the law says, our analysis suggests schools across Illinois aren’t doing a very good job — and it’s students who’re paying the price.

If every school district in Illinois met the minimum benchmark to not be suspected of under-identifying youth experiencing homelessness, Illinois would have identified more than 92,000 students experiencing homelessness in 2021. But because Illinois only identified about 37,000 students experiencing homelessness in 2021, we estimate there are potentially 55,000 more students experiencing homelessness legally entitled to federal and state support who haven’t been identified yet.

The effects of homelessness can be great; homeless youth graduate at lower rates than their housed peers. In 2021, the gap in graduation rates in Illinois was at 20%, according to data from the U.S. Department of Education.

“When a person doesn’t have housing they also very often don’t have access to bathing or getting food the way they need it,” said Jean Terdic, Housing Intake and Aftercare Manager at 360 Youth Services, an organization that provides shelter and counseling for Naperville youth and families experiencing homelessness. “And when they don’t have those basic needs, it’s extremely hard to be able to focus on things like school when you’re trying to survive.”

Listen to this quote:

Experiencing homelessness can also make it difficult to access resources others may take for granted, such as showering, accessing bathrooms and doing laundry.

“They often have to carry their belongings with them everywhere, which means they can’t have many belongings,” Terdic said. “They struggle to have access to a computer and the Internet which can make it difficult with schoolwork, among other things. Sleep quality, in general, is very bad, because they [have to move] place to place.”

To identify youth experiencing homelessness, school districts are required by law to work with nearby shelters. But the vast majority of students experiencing homelessness do not live in shelters or on the street. Instead, they’re often staying temporarily with family or friends.

“Homelessness among children and youth is very hidden,” Duffield said. “When you think of homelessness, you think of Chicago, people outside [on the streets]. For children and youth and families, [homelessness] is staying with other people temporarily. It’s moving from place to place. It doesn’t look like what we typically think of as homelessness.”

Listen to this quote:

In some cases, families and youth hide their situation because they don’t want anyone to know, Duffield said.

“There’s fear and stigma and shame that families and youth who are homeless feel,” Duffield said. “[Sometimes, parents] fear their kids may be taken away or something bad might happen to them.”

Because students who are doubling up are less visibly homeless, identifying them can be difficult.

“Oftentimes the students are not aware of the McKinney–Vento [Homeless Assistance Act] and they don’t necessarily realize that they would be considered homeless because they have a place to stay each night, even though it’s a different place,” Terdic said.

In Naperville Community Unit District 203, various counselors, psychologists, social workers and administrators at every school work together to identify students experiencing homelessness.

“We get information about families through our social workers or counselors or psychologists or our teachers and administrators,” said Kimberly Dreisbach, District 203’s Supervisor of Social Work and one of the district’s two homeless liaisons. “They’ll work with families [if] they hear about something.”

Counselors, social workers and other staff members are also trained to look for signs of homelessness, such as if a student is falling asleep in class, chronically tardy or wearing the same clothes to school every day.

“We share information [about the signs of homelessness] with our administrators, social workers and counselors,” Dreisbach said. “[We give] reminders of what to look for, [such as] students moving from place to place every night, or [students mentioning] ‘we’re not sure where we’re going to be’ or different feedback or conversations with families.”

District 203 also works with local organizations that support homeless youth and families, such as 360 Youth Services, the only youth shelter in Naperville.

“Often the school would reach out to me and let me know that a student had approached a teacher or social worker and let them know that they’re struggling with their housing,” Terdic said. “Sometimes, the school may not be aware [a student has] been admitted into our program. In those cases, the case manager would get consent from the student and reach out to the school’s homeless liaison.”

Every student identified as homeless, whether through 360 Youth Services or school staff, is then granted certain supports, such as free school lunch and free daily transportation.

“We are willing and able to help anyone who is willing to make it known [that they are experiencing homelessness],” said Alex Mayster, Executive Director of Communications at District 203.

Still, the process isn’t perfect. In the 2020-21 school year, District 203 identified 160 students experiencing homelessness, which is equivalent to about six percent of its low-income population and places District 203 below the benchmark our analysis defined as “likely to be undercounting homeless youth.”

“I definitely think we have not identified everybody under [the U.S. Department of Education’s definition of homelessness],” Dreisbach said. “We’re still working to make sure that our families know that we’re here to support them.”

But while District 203 has an entire team involved in identifying homeless youth, federal law only mandates that the homeless liaison be “able” to do their job. For less-affluent districts, the responsibilities of “homeless liaison” are often placed upon another staff member who already has a full-time job.

In dozens of districts, Central Times found the homeless liaison is simultaneously the superintendent, principal, school nurse or otherwise, each with their own full-time responsibilities on top of their role as the homeless liaison, potentially making it difficult to dedicate the time that student outreach requires.

“It’s very definitely an issue, making sure that the liaison has enough time [and] enough capacity [to] fulfill their responsibilities,” Duffield said.

State and federal law mandates that districts put up posters and post information online to inform students experiencing homelessness of available support and of their rights. But for dozens of districts, Central Times was unable to identify the district’s homeless liaison or locate any information about rights and supports afforded to students experiencing homelessness through internet searches or by looking at their website.

Weak enforcement

The federal government largely delegates the enforcement of the McKinney–Vento Homeless Assistance Act to individual states, and the Illinois State Board of Education (ISBE) monitors each school district on a three-year cycle, but that monitoring does not include determining if homeless liaisons have the time or capacity to carry out their responsibilities.

In an email, a spokesperson for the ISBE acknowledged “many districts have not yet posted [McKinney–Vento] information on their website as of yet,” despite state and federal law requiring schools to do so. In March, the ISBE issued a letter explaining the law to all McKinney–Vento liaisons, and the ISBE has since modified monitoring documents to include checking if schools have posted the necessary information required by law. Still, due to the monitoring cycle, it could be up to three years before some districts are monitored with new compliance documents.

Furthermore, unlike other states such as Michigan and Florida, which utilize benchmarks and enrollment data to determine if a school district is potentially under-identifying homeless youth, the ISBE does not determine if school districts are likely undercounting homeless youth, a spokesperson wrote in an email.

Implementing a benchmark to identify school districts at risk of under-identifying students experiencing homelessness would be helpful, Erb-Downward said. The benchmark would not be a mandate to identify a certain number of students, but rather a “gentle prod” for districts that are below the benchmark to look at where they could improve.

“Let’s take a moment to look at things that don’t make sense,” Erb-Downward said. “If you have a district where you have 20% of kids living in poverty and you have identified 0 students experiencing homelessness, that doesn’t make sense.”

But whatever policy is implemented, authority figures have little recourse if a district is not in compliance with the law.

“Really the only kind of enforcement that exists is ‘okay, you’re not meeting the guidelines and so you’re going to lose your funding,’” Erb-Downward said. “For districts already struggling with identifying homelessness, that’s not really going to help.”

Inadequate funding

Illinois received about 3 to 4 million dollars in federal funds each year between 2016 and 2019 for supporting homeless students, about $60 to $80 per student experiencing homelessness. That money is the only federal funding schools get to pay for a year’s worth of transportation, school materials, clothes and other support. It isn’t always enough, Erb-Downward said.

“Transportation can be incredibly expensive,” Erb-Downward said “It’s a lot to put on school districts, and in some ways, there’s almost a disincentive to identify students [experiencing homelessness].”

Furthermore, because federal funds are almost entirely disbursed based on a competitive-grant basis, some school districts miss out. Between 2016 and 2018, anywhere from 82 to 189 school districts received no federal funding at all. Research has shown the likelihood of under-identification is much higher in schools without dedicated homeless education funding.

A new ‘hope’

In the 2022-23 school year, Illinois identified 42,387 youth experiencing homelessness, a 9% increase over pre-pandemic counts, a spokesperson for the Illinois State Board of Education wrote in an email. While that number is still less than half of the estimate from our analysis — 92,000 — the count has been increasing every year since the pandemic.

The American Rescue Plan, which was signed into law on March 11, 2021, allocated $33 million in federal funding for students experiencing homelessness in Illinois.

“It helps to have financial incentives so schools understand that students [experiencing homelessness] are not liabilities, but they actually are students who contribute to the school and that there’ll be funding to help keep them in school,” Duffield said. “When there’s more [financial] support, we see identification go up. That shouldn’t be rocket science. We’ll see maybe a year from now the correlation between the districts that use those funds to actually advance capacity, add hours, and [the] identification [of students experiencing homelessness].”

Organizations across Illinois have also worked to better identify students experiencing homelessness. In their 2019-24 contract, the Chicago Teachers Union negotiated to support staff dedicated to working with students experiencing homelessness in schools with high rates of student homelessness.

In addition, the Illinois General Assembly passed HB 3116 on May 4, which mandates all school personnel be trained to identify signs of homelessness.

“Hopefully, with the additional training, teachers will be equipped to report any suspected issues to the liaison who can help families get connected with resources and community organizations,” said Katie Stuart, State House Representative and the original sponsor of the bill. “Teachers want their students to have every opportunity to succeed in the classroom, and the training will help them to be a part of supporting their students and their families.”

The bill now awaits signature by the governor.

“I think this legislation is a great step in making sure we identify our students experiencing housing insecurity,” Stuart said. “We need to make sure we invest in our schools, so that they can have the social workers and nurses and counselors on staff who can provide further assistance to these students.”

If you are a student in Illinois and fit the U.S. Department of Education’s definition of homeless, you can find your district’s McKinney-Vento homeless liaison here. Illinois youth experiencing homelessness can read about their rights here.

Reporting and data analysis by Nathan Yuan. Nolan Shen and Ziad El Bego contributed to data cleaning and research.

Diane Nilan • May 27, 2023 at 5:20 am

I’m in (delighted) shock reading this story, not because of the disturbing revelations of student homelessness in Illinois, but because Naperville Central students did what no other journalists have done.

The need for a report of this nature, in every state, has gone unmet since the federal reauthorization of the McKinney-Vento Education for Homeless Children and Youth Act in 2002. The provisions in this law are based on the Illinois Education for Homeless Children Act passed in 1994. That law originated in Naperville-Aurora after a family from Naperville staying at the shelter at Hesed House in Aurora was denied access to their schools of origin in District 204.

School stability is vital for children and youth experiencing the upheaval of homelessness. Since 2005, I’ve interviewed hundreds of homeless kids across the country, most from non-urban areas, who validated the need for school stability and support offered by effective McKinney-Vento programs.

My one-woman nonprofit, HEAR US Inc., based in Naperville, has helped countless schools across the country better identify, understand and serve the millions of families and youth experiencing homelessness.

The trouble, in addition to skyrocketing rates of unaddressed homelessness, is districts failing to identify and assist homeless students, as these astute students have documented.

The appalling number of unidentified students represents an untapped resource in our country. With support, these young people can turn their hardships into opportunities to better our communities. Without support, they are at great risk of struggling to be productive, self-sustaining members of society. Those of us with the abilities and resources to help have a choice.